|

| Shell’s Prelude FLNG (left) has been designed to replicate an onshore LNG facility in one-quarter of the area typically used on land. Once in place, the facility will process 473 MMcfd of LNG as well as 35,000 boed of condensate and LPG (courtesy of Shell). BG Group started loading the first cargo of LNG from its QCLNG facility onto the Methane Rita Andrea on Dec. 28 (center, courtesy of BG Group). Other LNG projects under construction include Gorgon (right) and Wheatstone in Western Australia, which, together, will add 23.9 million tonnes/year of capacity by 2016 for gas from the Carnavon basin (courtesy of Chevron). |

|

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is the central theme for the energy industry in Australia and Southeast Asia, where plentiful natural gas and accessible Asian customers present great opportunities. LNG projects have attracted the lion’s share of capital in the region, and the drive to create LNG capacity demonstrates the vast scope and long-term vision of oil and gas companies, and their host countries.

Shell’s Prelude floating LNG (FLNG) production, storage and offloading facility epitomizes the ambition and audacity of the effort to make LNG as universal a commodity as crude oil.

Prelude has been touted as the largest ship ever built. At 1,601 ft, it is longer than the Petronas Towers are tall, and, when completed, it will displace 600,000 tons. When it is moored at Prelude field, 125 mi off the coast of North West Australia, in 2017, it will gather natural gas from subsea wells, condense it to LNG and transfer it directly to LNG tankers.

Prelude FLNG was designed to replicate an onshore LNG facility in one-quarter of the area typically used on land. Its gas processing components will be contained in 14 modules, which will be lifted onto the massive hull at the Samsung Heavy Industries shipyard in Geoje, South Korea. Standardized components used on Prelude could provide a template for building future offshore LNG plants, in a shorter time and with less environmental impact than equivalent onshore facilities, Fig. 1.

|

| Fig. 1. 3D rendering of completed Prelude FLNG. Image courtesy of Photographic Services, Shell International Ltd. |

|

Once in place, the Prelude FLNG facility will process 473 MMcfd of LNG—enough to supply the city of Hong Kong—as well as 35,000 boed of condensate and liquid petroleum gas. While the $13-billion Prelude is an impressive achievement, it is the smallest of seven LNG facilities under development in Australia.

ENERGY DEMAND GROWTH DRIVES INVESTMENT

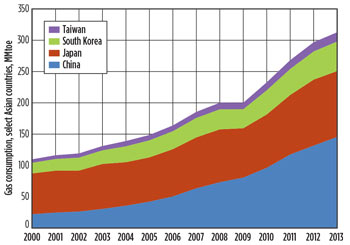

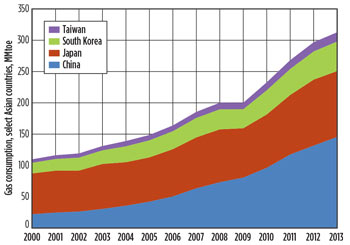

More than $300 billion have been invested, or committed, for LNG facilities in Australia and Southeast Asia. This investment was driven by the fast-growing economy of China, and dependence on imported energy in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. The 2012 earthquake in Japan, and the resulting damage to the Fukishima nuclear plant, provided an incentive for the Japanese to generate more electricity with natural gas. Natural gas consumption in these four countries tripled from 2000 to 2014, Fig. 2.

|

| Fig. 2. Gas consumption in select Asian countries (million toe). |

|

The technology for processing and transporting LNG has improved greatly since LNG was first transported by tanker in 1964. In 2013, there were around 380 LNG tankers in operation worldwide, which transported a total of 240 million tonnes of LNG. By 2018, more than 520 LNG tankers are expected to transport more than 330 million tonnes of LNG. Over the past five years, the number of LNG importing countries has increased to 29 from 18. Around 30% of the global LNG volume is now traded in spot and short-term trading markets.

ASIAN MARKETS

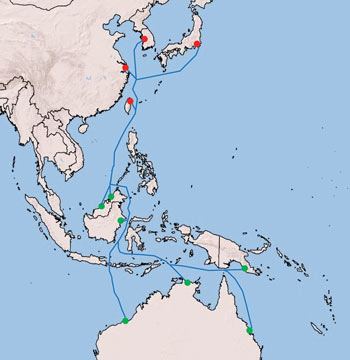

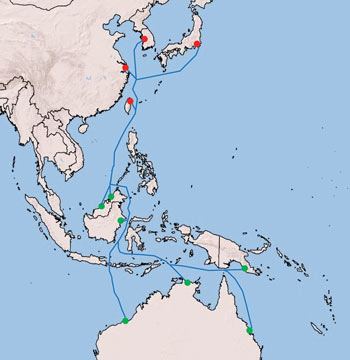

Australia and Southeast Asian LNG exporters have ready access to the industrial countries of Asia, including China, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, the region’s major LNG customers, which also purchase LNG from the Middle East, Africa and Sakhalin, Russia. Figure 3 shows the major trade routes for LNG from the four export terminals now operating in Australia and the export terminals in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei and Papua New Guinea. The Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea are highly trafficked by both LNG and crude oil tankers, making these shipping lanes critical to energy security in the region, Fig. 4.

|

| Fig. 3. Australia-Pacific LNG shipping routes. |

|

|

| Fig. 4. The strait of Malacca and South China Sea are important for the region’s energy security. Courtesy of U.S. EIA. |

|

LOWER OIL PRICES AND SHALE

Most LNG delivery contracts with Pacific Rim customers are take-or-pay contracts indexed to the price of oil, with natural gas prices set at around 14% of the Brent crude price per million BTU. Because of the drop in crude prices in the second half of 2014, Asian customers are paying $10 or less per million BTU compared to $16 in January. An extended period with oil prices below $60/bbl would impact the return on investment for operating LNG projects, and could cause delays in projects under construction. The slowdown in China’s growth, and the ongoing recession in Europe, may continue to exert downward pressure on oil prices and LNG prices tied to them.

U.S. shale gas entering the market also could bring price competition, as new terminals along the U.S. Gulf Coast begin operating later this decade. LNG from U.S. projects is expected to sell for $11 to $12 per million BTU; however, instead of negotiating take-or-pay arrangements, U.S. exporters are offering toll contracts, in which customers are obligated to pay a lower fixed rate of, perhaps, $3 per million BTU, if orders are canceled before delivery.

AUSTRALIAN LNG PROJECTS

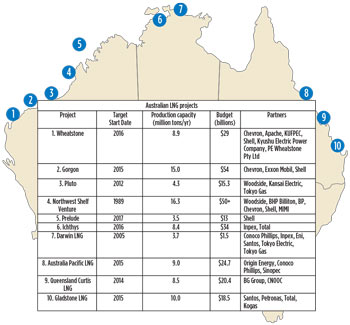

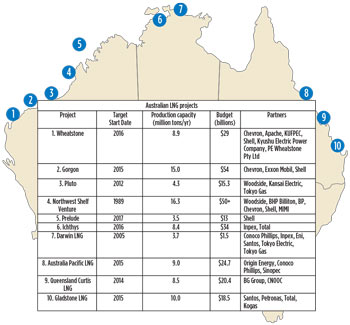

The Asia-Pacific region has added the most LNG capacity in the past several years, and more than two-thirds of current global LNG investment has been made in Australia, Fig. 5. Four Australian LNG export terminals were in operation at the end of 2014, with six more under construction. According to the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association, Australia has total estimated gas reserves of 816 Tcf and an annual domestic consumption of 1.1 Tcf. So, despite regional shortages in eastern Australia, there is plenty of natural gas for export.

|

| Fig. 5. Australian LNG projects. Courtesy of Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association. |

|

Operational LNG projects include the North West Shelf Venture, which began shipping LNG in 1989, and currently has five production trains. The Darwin LNG facility began production in 2006 and has one train in operation. The Pluto project started up in April 2012 with one production train. The Queensland Curtis LNG project, which began operation in 2014, is the world’s first plant to liquefy coalbed methane (CBM).

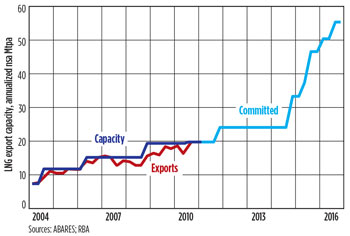

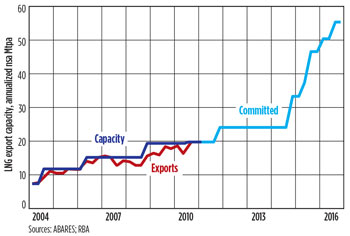

Projects under construction include Gorgon and Wheatstone in Western Australia, which, together, will add 23.9 million tonnes/year of capacity by 2016 with gas from the Carnavon basin. The Ichthys project in northern Australia will add another 8.4 million tonnes/year. In addition to the Queensland Curtis LNG project, the Gladstone LNG and Australia Pacific LNG projects will tap CBM from the onshore Surat-Bowen basins in Queensland, for a combined total capacity of 27.5 million tonnes/year, scheduled for the end of 2015. According to Reserve Bank of Australia projections, the rapid addition of LNG trains is expected to more than double total Australian export capacity from 23.9 million tonnes in 2013 to over 55 million tonnes/year by the end of 2016, so the country would be second only to Qatar in LNG export volume, Fig. 6.

|

| Fig. 6. Australian LNG export capacity. Courtesy of Reserve Bank of Australia. |

|

The ambitious scale of Australia’s LNG capacity expansion has strained the country’s workforce and supply chain. With seven large LNG projects under construction at the same time, skilled labor has been in short supply, resulting in delays and cost escalation. Ramping up CBM production enough to satisfy export commitments, as well as domestic gas demand in eastern Australia, also has been a challenge.

The decline in oil prices also has made some operators and energy consumers rethink their LNG strategies. Apache Corp. has decided to sell its 13% stake in the Wheatstone project, and Woodside announced that it was postponing an investment decision on whether to go forward with an FLNG facility in its Browse field, off Australia’s northwestern coast.

In December, Reuters reported that China’s Sinopec was seeking buyers for portions of its long-term LNG import contracts because of China’s slowing economy, increasing Chinese gas production, and low LNG spot market prices.

PAPUA NEW GUINEA LNG—FIRST SHIPMENT

Exxon Mobil PNG Ltd. (with 32%) is the lead partner in the Papua New Guinea LNG project near Port Moresby. Another partner, Oil Search (29%) developed the gas fields in Papua New Guinea’s Southern Highlands, Western, Hela, Gulf and Central provinces. These fields are connected to the gas liquefaction plant by 435 mi. of pipelines. The $19-billion facility includes a gas conditioning plant, liquefaction and storage tanks.

Aside from Sinopec, Osaka Gas Company Corp., CPC and Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) have contracted for PNG LNG’s production. The project’s first LNG cargo arrived in Japan, for TEPCO, on May 25, 2014. When its second train went into production in July, PNG LNG reached its full capacity to liquefy 6.9 million tonnes/year of LNG.

MALAYSIA: SECOND LARGEST LNG EXPORTER

Malaysia, currently the world’s second largest LNG exporter after Qatar, delivered 27 million tons in 2013 to Pacific Rim customers. Petronas is building the ninth LNG train at its complex in Bintulu. The new production train has a 3.6 million tonne/year capacity and will bring the Petronas LNG facility’s total output to nearly 28 million tons/year.

In addition, Petronas is constructing two FLNG vessels to gather and liquefy gas from fields offshore Sarawak and Sabah. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the first FLNG will be located off Sawarak near the Bintulu complex, and will collect gas from Kanotwit field and is expected to come online with a 1.2-million tonne/year capacity in 2016, a year ahead of Shell’s Prelude. The second FLNG will liquefy gas from Rotan field northeast of Sabah in the South China Sea. The terminal will have a capacity of 1.5 million tonne/year and could serve some domestic demand in Sabah by reprocessing at the proposed Lahad Datu regasfication plant. The project is scheduled to be online by 2018.

Petronas also has made other recent improvements to its LNG infrastructure. Malaysia commissioned a 3.8-million tonne/year regasification terminal with two floating storage units at Melaka Island, 2 mi off the Sungdai Udang port. The terminal, connected to the Peninsular Gas Utilization pipeline network, received its first LNG cargo in August 2013. Regasification terminals are required, because Malaysia’s gas reserves and demand are not distributed evenly among its geographically separate Western Peninsula and Sabah and Sarawak regions.

In addition, the first phase of the Pengerang Independent Deepwater Terminal, a $1.3-billion, bi-directional LNG terminal, was completed in early 2014.

INDONESIA: TREND TOWARD REGASIFICATION

Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous nation, has a growing economy and increasing domestic energy needs. This demand and declining production from its Arun field have reduced LNG exports by 40% from their peak volume in 1998. And, like Malaysia, Indonesia has invested in regasification facilities to distribute natural gas throughout its vast archipelago.

Pertamina’s liquefaction plant and LNG terminal at Bontang, East Kalimantan, is one of the world’s largest with a capacity of 1.1 Tcf/year. The BP-operated terminal at Tangguh, Papua, is about half that size at 650 Bcf, and BP has submitted a proposal to expand capacity by another 182 Bcf by 2019. The Indonesian government has indicated that LNG from these two facilities will be called on to supply domestic demand.

Two new LNG liquefaction plants are being built—Donggi-Senoro (scheduled for operation in 2015) and Sebong (planned for a 2017 startup), both in Sulawesi. An FLNG, which Inpex plans for Abadi field in the Arafura Sea, has been pushed back to 2019, according to PFC Energy.

The EIA reported that the Indonesian government began its LNG regasification program using a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) at Nusantara, West Java, to regasify LNG supplied by the Bontang and Tangguh terminals, Fig. 7. A second FRSU, also built by Pertamina and PGN, went into operation in 2014, near Lampung in southern Sumatra, to fuel an electric power plant.

|

| Fig. 7. Indonesia has invested in regasification facilities to distribute gas around the nation. Courtesy of EIA, IHS EDIN. |

|

IHS Global reported that Pertamina is converting its Arun LNG liquification plant to a regasification terminal, which was scheduled to come online in late 2014, to supply gas for power generation and fertilizer production.

Pertamina and state electricity firm PLN also have planned eight small LNG regasification plants (with a total capacity of 67 Bcf/year) to enable electrical generation in eastern Indonesia. The regasification plants will receive domestic and imported LNG.

EOR PROJECTS TARGET DECLINING PRODUCTION

While natural gas offers the greatest growth potential, several countries in the region have been working to stem the decline in their oil production.

Malaysia has successfully leveled off its oil production decline through large-scale EOR projects, EIA reports. Petronas and Shell have partnered on the world’s largest offshore EOR project that includes nine fields in the Baram Delta offshore block and three fields in the North Sabah area. The combined investment of $12 billion in this project is expected to improve production by 90,000 bopd through chemical injection. Some of the associated gas produced in the Baram Delta will be reinjected to sustain reservoir pressure; the rest will be sold to domestic and international markets.

Former OPEC member Indonesia has seen its oil production drop 575,000 bpd since 2000, to 880,000 bpd in 2013. Indonesia’s effort to reverse this trend has been hampered by regulations and licensing requirements that have discouraged foreign investment, aging infrastructure and disappointing results in deepwater exploration programs.

Despite these headwinds, Indonesia has made progress with the help of international partners. Chevron—operator of the South Sumatra Duri and Minas fields that date back to the 1950s—has conducted large steamflood EOR projects to stem the production decline. In the East Java basin, Pertamina and PetroChina have a joint operating agreement to increase production by 10,000 bopd.

Also in East Java, Exxon Mobil is operating the Cepu Block, which was producing 40,000 bopd in 2014, but is, eventually, expected to produce 165,000 bopd from 49 wells.

UNCONVENTIONAL RESOURCES

Unconventional resources also have potential to add significant gas and liquid production in Australia, and to a lesser extent in Indonesia. Australia is already a major producer of CBM, with 33 Tcf of economically recoverable methane resources, according to Geoscience Australia.

Shale gas and oil show promise for development over the next decade. EIA estimates that Australia has 437 Tcf of unproved, technically recoverable, shale gas resources, and 17.5 Bbbl of unproved, technically recoverable, shale oil resources, in the Cooper, Canning, Marborough, and Perth basins. An Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA) report in 2013 found that Australia could have more than 1,000 Tcf of recoverable shale gas. Australia Geoscience is more circumspect, stating, in its 2014 Energy Resource Assessment, that the country’s shale resources “remain to be defined.”

Australia’s first commercial shale gas well was drilled in 2012 by Santos in the Cooper basin, which has oil field infrastructure in place. ConocoPhillips and PetroChina recently suspended their shale gas evaluation program in the Canning basin after disappointing results and rapid gas decline rates, the Australian Financial Review reported. The Chevron JV in the Cooper basin, with Beach Energy and Icon Energy, had similar results with its test wells, but continues to evaluate prospects. In August, the New South Wales government gave AGL Energy approval to start hydraulic fracturing in a 110-well pilot program to test gas at Glouster in the Perth basin.

Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources estimates that the country has CBM reserves of 453 Tcf, based on preliminary studies. In 2013, Singapore-based Dart Energy and Indonesian PT Energi Pasir Hitam started exploring for CBM in East Kalimantan in 2013, with the goal of supplying power plants and the Bontang LNG facility. The government anticipates CBM production to reach 183 Bcf/year by 2020.

EIA estimates that Indonesia has 46 Tcf of total recoverable shale gas resources. While there is, currently, no shale gas production in the country, Indonesia has awarded Pertamina two shale gas production sharing contracts for the Sumbagut Block, in North Sumatra. Operating costs are high in this region, and it remains to be seen whether commercial shale gas production is feasible.

|