2022 Forecast: Oil and gas in the crosshairs

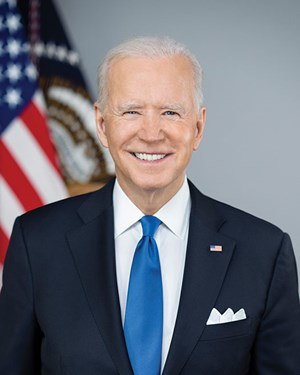

Joseph Biden campaigned against fossil fuels, recommended “throwing oil executives in jail,” and wasted little time in following through as President, Fig. 1.

For example, thus far, he has recommitted the U.S. to the Paris Climate Agreement; rescinded the construction permit for the Keystone XL oil pipeline; and signed an Executive Order (EO) requiring that all electricity the federal government uses be “100% carbon-free” by 2030. In addition, he ordered federal agencies to reinstate over 100 environmental regulations rolled back by former President Trump; suspended oil leasing in Alaska; suspended permits to drill in oil and gas (O&G) leases on federal lands; asked the Federal Trade Commission to investigate whether O&G companies are responsible for increasing gasoline gas prices; and plans to block O&G leasing on 11 million acres of Alaska’s North Slope—nearly half of a 23-million-acre reserve set aside for energy development decades ago.

Biden’s administration also planned to close the L5 pipeline, which carries O&G liquids from Canada to the U.S. but reversed itself in the face of intense criticism. The anti-energy policies may be working: Active U.S. rigs totaled 586 on Dec. 31, 2021—a 27% decrease from the Dec. 27, 2019, count of 805. The administration’s war on the O&G industry continues with death by a thousand cuts.

Biden’s senior environment and energy positions are populated by climate alarmists hostile to the O&G industry, Fig. 2. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland co-sponsored the Green New Deal (GND), opposes O&G production on federal lands, and supports a fracing ban. White House National Climate Advisor Gina McCarthy was architect of Obama greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) rules, which were repealed by the Trump EPA. John Kerry, former Obama Secretary of State, is Special Presidential Envoy for Climate—he drafted the 2016 Paris Climate Accord and has labeled climate change as “the most serious threat to mankind.”

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg labeled climate change a national emergency and advocates the GND. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen advocates CO2 emissions taxes and cap-and-trade; has labeled climate change an “existential threat;” and created a Treasury climate change team. Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Gary Gensler is imposing stringent ESG disclosures; increased corporate reporting on GHG emissions; and “evaluation and pricing of climate risk.”

Meanwhile, Stanford University professor Sally Benson serves as deputy director for energy and “chief strategist for energy transition” at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. One of her top priorities is ensuring a swift transition to a “clean energy economy.” She noted that President Biden’s goals of 100% clean electricity by 2035, and eliminating CO2 by 2050, will “require a total transformation of America’s industrial and transportation systems.”

However, industry dodged a bullet when Saule Omarova, under criticism, withdrew her nomination to be Comptroller of the Currency—the U.S. federal bank regulator. Dr. Omarova, who attended Moscow State University under a Lenin Scholarship, stated that fossil fuel producers should “go bankrupt, if we want to tackle climate change.”

The administration can be tone-deaf and clueless; for example:

- In promoting his efforts to reduce gasoline prices, Biden stated that “Americans would save money on gas, if they owned electric cars”—electric vehicles (EVs) currently comprise 1% of U.S. vehicles.

- At a press conference, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm admitted that she did not know how much oil the U.S. consumes per day (answer is 18.2 MMbbl). At an energy conference, she stated “We have to add hundreds of gigawatts to the grid over the next four years. It’s a huge amount. And there’s so little time.” U.S. installed electric generating capacity totals 1,100 GW. To claim that the U.S. should add “hundreds of gigawatts” to the grid in four years is ludicrous.

The administration’s energy policies are embarrassing. Faced with politically damaging, increased gasoline prices in late 2021, officials implored OPEC to increase oil production. Is the administration upending five decades of U.S. energy policy and attempting to increase U.S. dependence on the OPEC cartel? At the same time, the administration is implementing policies to decrease U.S. oil production. It also initiated a “Buy American” program that will “support domestic production of products critical to our national and economic security.” It is hard to imagine a product more important than oil to “U.S. national and economic security.”

The administration wants companies to pay more to drill on federal lands and waters. The Interior Department recommends increasing the federal royalty rate from the current 12.5% and increasing the bond that companies must post before they start new wells. Raising the royalty rate to 18.75% for drilling in deep waters offshore would cost companies an additional $1 billion/yr., and a royalty rate of 25% for on- and offshore drilling would double the cost to $2 billion annually.

Interior officials also want to incorporate the “social cost of carbon” into the price of permits for new O&G extraction. The administration set this at $51/ton of CO2 but suggested the estimate could go higher—the Interagency Working Group recommended a 2022 estimate of nearly $80/ton of CO2.

This coincides with efforts from congressional Democrats to pass a suite of O&G leasing provisions in the Build Back Better budget deal, Fig. 3. The version passed by the House included provisions that would raise the minimum royalty rate for onshore drilling, for the first time in a century; shorten the length of leases from 10 to five years; and eliminate a program that allows sales of leases for as little as $1.50/acre. However, the bill did not pass the Senate. The Interior Department can increase royalty and bonding rates unilaterally but embedding higher rates in legislation would shield the policies from court challenges.

In June, the administration submitted a budget proposal that would have eliminated many fossil fuel “subsidies.” That wish list of tax changes dwindled in subsequent months, but the Build Back Better proposal included two provisions that would cost industry dearly. One would eliminate an O&G exception to a 2017 law that taxes foreign profits of U.S. companies, and this could cost industry as much as $8.5 billion annually. The proposal also would have reinstated the tax on crude oil designed to support EPA’s Superfund program clean-up efforts, which expired in 1995. This could cost industry an additional $4 billion annually.

As part of the Build Back Better (BBB) plan, a new tax starting in 2023 would be levied on natural gas production that would translate into higher heating bills. The fees depend on where the natural gas is produced and vary depending on methane releases. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the new “methane fee” would cost industry nearly $1 billion annually, and the natural gas industry contends that the fee will be paid by consumers: “New fees or taxes on energy companies will raise costs for customers, creating a burden that will fall most heavily on lower-income Americans.” The new fee could translate into a 17% increase in energy prices for homes utilizing natural gas.

DOE warned that U.S. households using natural gas would face cost increases of 30% to 50% in 2022. DOE estimated that the average family relying on natural gas heat would pay $746 between October and March, compared to an average $570 in 2021. The methane fee would add 17% to this cost. This is a regressive tax, since the energy burden for low-income families is three times higher than of more affluent households. Further, once the methane tax is enacted, it can be increased over time and, combined with new methane regulations, will continue to increase costs. The House bill was not passed in the Senate. It remains to be reintroduced, although Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) on Feb. 3 reiterated that as far as he was concerned, the BBB legislation was dead.

Under the guise of regulating GHGs, EPA announced new, more stringent fuel-efficiency standards for cars and light-duty trucks. The new standards begin with the 2023 model year, and 2026 vehicles will be required to achieve a fleet-wide average of 55 mpg, an increase of more than 35% from the 2021 standard. EPA intends to impose even more stringent standards beyond 2026. The action is the latest in the administration’s efforts to force Americans to buy EVs, and manufacturers contend that the new standards cannot be met without “more generous government EV subsidies.” However, the real purpose is to impose an EV mandate by regulatory fiat, since there is no chance that Congress will ban sales of internal-combustion vehicles.

Biden wants to ensure that 50% of new car sales are electric by 2030 and that all additions to the federal government’s vehicle fleet are electric by 2035. Meeting the new standards will be difficult, because consumers do not want EVs. Through the first nine months of 2021, 460,000 EVs were sold in the U.S.—half of them in California. By comparison, Ford sold 535,000 pickup trucks during this same period.

Restriction of leasing and permitting for O&G drilling on federally owned lands and in federally owned waters will be a major 2022 court battle. The first drilling lease sale held under the administration, which offered 80 million acres for auction in the Gulf of Mexico, was contentious. The administration delayed that lease sale as part of its moratorium on new O&G leasing. However, after a court halted the moratorium, the sale went through, much to the chagrin of environmental groups. These groups oppose future sales, including a proposal to auction ocean parcels near Alaska’s coast and an onshore lease sale in New Mexico.

But in yet another twist on Jan. 27, U.S. District Judge Rudolph Contreras in Washington, D.C., vacated the lease sale in a 67-page decision. He found that the Interior Department underestimated the climate impacts of the leases and conducting a further analysis wouldn’t overly harm the companies seeking the leases. “The leases have not become effective, and no activity on them is taking place,” the judge wrote. If the leases were to take effect, it would be much harder to cancel them, he added.

The issue, over which waters should be regulated, has been an intense partisan battle for years. In 2015, the Obama administration expanded coverage to small bodies of water, but this was repealed during the Trump administration. The Biden administration will propose to regulate more waters, but the specifics are unclear. Rule opponents will likely sue, and if environmentalists do not think the rule goes far enough, they will likely also challenge it.

During 2022, the battle over power plant emissions will ensue through regulations and at the Supreme Court. EPA is expected to propose rules regulating emissions from new and existing power plants, to be finalized in 2023. EPA was likely to have a relatively blank slate after a lower court struck down a Trump-era rule—the Affordable Clean Energy Rule (ACER). ACER gave states more time and authority, compared to the Obama administration’s rule (the Clean Power Plan), to decide how to reduce emissions from fossil fuel plants.

But in October 2021, the Supreme Court agreed to consider EPA’s authority to regulate CO2 emissions under the Clean Air Act, a decision which, according to court observers, “is the equivalent of an earthquake. It could sharply curtail or eliminate the administration’s ability to use the Clean Air Act to significantly limit GHGs.” Petitioners asked the court to review the ruling, with North Dakota arguing that the court should reinstate the Trump-era rule. The Biden administration urged the justices not to hear the case.

There are two sleepers that require monitoring. First, Jerome Powell, the recently reappointed Federal Reserve chair, stated that climate stress tests for banks will “be a very important priority” in supervision—even though climate policy is not part of the Fed’s mandate. This could have the Fed using stress tests to force banks to reduce and eventually eliminate O&G financing. Banks would have to adjust their balance sheets to account for the risks from government climate policies, such as mandates, regulations, and carbon taxes.

Accordingly, to pass the climate stress tests, banks would have to liquidate O&G assets. This is political allocation of capital, which also is not the Fed’s job. Also at the Fed, Sarah Bloom Raskin was nominated to be vice chair of Supervision. She has stated that U.S. regulators should use their existing powers to mitigate climate risk and “has specifically called for the Fed to pressure banks to deny credit to traditional energy companies.”

Second, federal spending is governed by Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR). Responding to a Biden Executive Order, the FAR Council wants to determine how climate change should be factored into federal spending. The federal government spends over $6 trillion annually, so this could have a major impact.

The FAR Council has issued an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rule Making, “Federal Acquisition Regulation: Minimizing the Risk of Climate Change in Federal Acquisitions.” It proposes that agencies give preference to bidders, who are reducing their GHG emissions, and require procurement officials to measure life cycle emissions of purchases. Suppliers would be required to report their GHGs and to reduce them.

The statutory authority for this is questionable, since Congress is supposed to enact legislation to do this—agencies cannot decide what to buy, based on a climate agenda. Trying to measure life cycle emissions for $6 trillion of procurement annually, and then basing procurement decisions on these measures, is absurd. However, that does not necessarily mean it will not happen.

It is likely that in November, Republicans will retake at least the House or Senate, and this will serve as a break on the administration’s anti-fossil fuel policies. Until then, it is going to be a long year for the O&G industry.

Dr. Roger Bezdek is an internationally recognized energy analyst and president of MISI, in Washington, D.C. He has over 30 years of experience in the energy, utility and environmental areas, serving in industry, academia and government. He has served as senior adviser in the U.S. Treasury Department; U.S. energy delegate to the EU and NATO; and as consultant to the White House, the UN, government agencies, and numerous corporations and organizations. He also is a long-serving contributing editor to World Oil.

- The last barrel (February 2024)

- E&P outside the U.S. maintains a disciplined pace (February 2024)

- Prices and governmental policies combine to stymie Canadian upstream growth (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- Executive viewpoint: TRRC opinion: Special interest groups are killing jobs to save their own (February 2024)

- U.S. drilling: More of the same expected (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)